Tropical Forecast 2024

We are sharing with the public our Tropical Forecast for 2024. Our forecast and methodology is a little different from other sources. We don’t do forecasts to impress other meteorologists. We produce forecasts for regular people just like us. When we focus on what we’re expecting for a Hurricane Season, we frankly don’t care much about how many storms are going to be out in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean that don’t hit land and don’t threaten the safety of most people.

So, our forecast has two main components. The first is how many storms get into the Gulf of Mexico. The reason for this is that if a storm gets into the Gulf, due to its shape, that storm is going to hit land somewhere more likely than not. The second component of the forecast is likely areas of landfalling storms. While all coastal areas should be paying attention to tropical weather during the Hurricane Season, we believe, based on previous weather patterns that some areas of the coast are more likely to be hit in certain years than in other.

So, here is our 2024 Tropical Forecast in a single graphic…

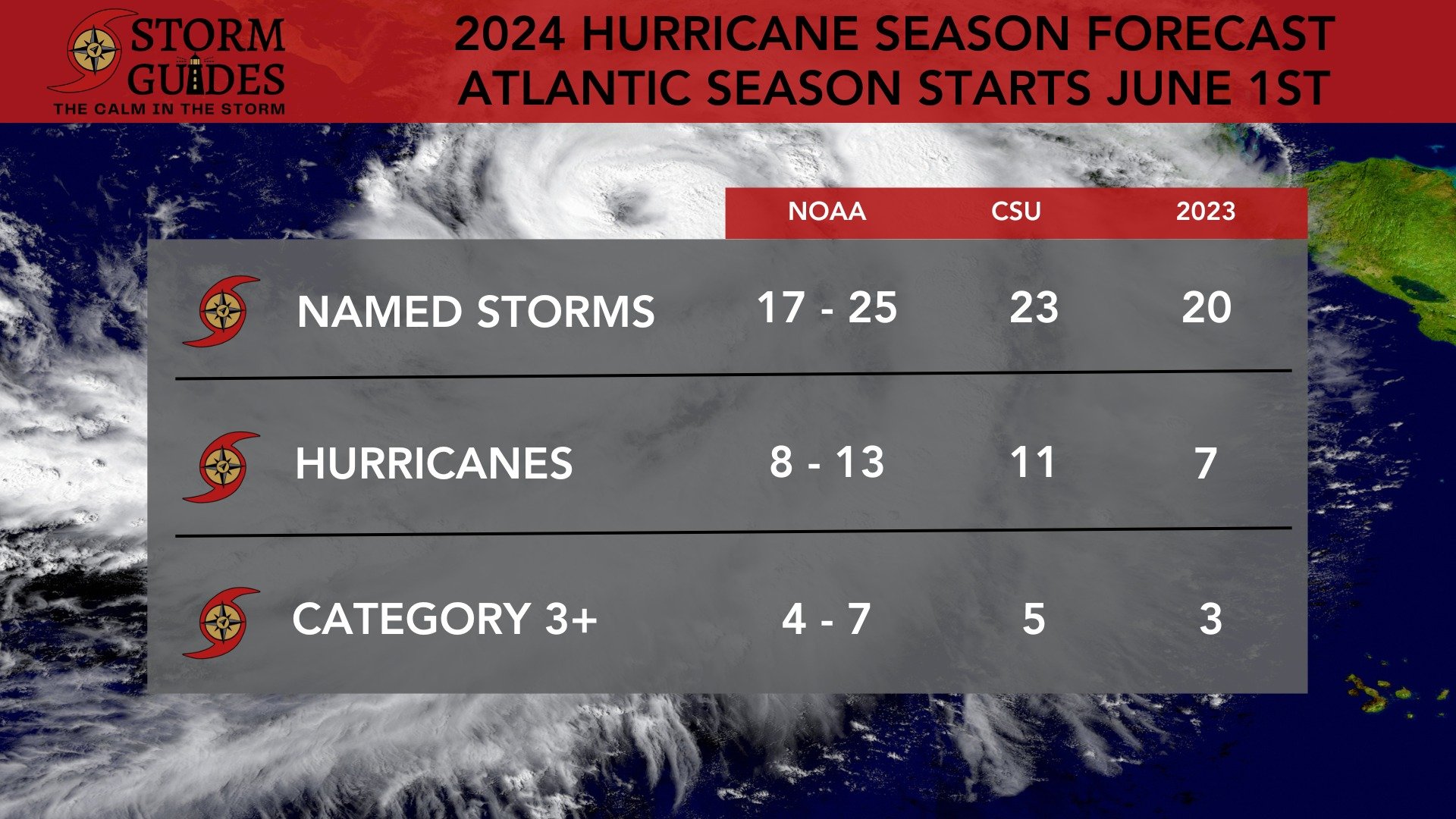

Just for a comparison, here is the official forecast from the National Hurricane Center. We’ve also included the forecast from Colorado State University, and the official storm totals from last year.

We don’t have any criticism of the numbers put out by the National Hurricane Center or by CSU. They seem reasonable given the setup with the temperature profile of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. I think you can see we just have a different idea of what we’re trying to accomplish with our forecast, and we hope it’s more valuable to you if you live anywhere along the coast.

So, how did we arrive at our forecast? We start by looking at how heat is distributed in the oceans. Atmospheric currents are driven by differences in heat, particularly heat in the oceans. You’ve no doubt heard about El Niños and La Niñas. These are the names given to changes in the distribution of heat along the equator in the Pacific Ocean. When there’s an excess build up of heat in that region, we call it an El Niño. When it’s colder than average, we call it a La Niña. Just the change in heat in this one part of the ocean has been shown to have a drastic impact on weather and climate around the world, and certainly across the United States.

This year, we are at the tail end of an El Niño, but most forecasts expect a La Niña to develop by the end of the Summer and continue through the fall. So, to put together this year’s forecast, we started by looking back at summers where we were leaving an El Niño and moving into a La Niña. That analysis led us to look at the years, 1954, 1964, 1973, 1983, 1995, 1998, 2007, 2010, and 2016.

The El Niño/La Niña cycle is not the only heat distribution pattern in the world’s oceans. It’s just the most famous. Another important cycle is the PDO, or the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. This deals with the Eastern North Pacific along the west coast of the United States, and it can disrupt the atmospheric flow across the country depending upon what phase it is in, cold or hot. The PDO is currently in its cold phase, has been for the past few years, and we expect it to remain in the cold phase through the summer. So we looked back at the years we had chosen as analogs to this season to match up the PDO. As a result, we eliminated 1983, 1995, 1998, and 2016 from the list because the PDO was in a warm phase during those years.

This left us with 1954, 1964, 1973, 2007, and 2010. When we looked at those years, a few patterns emerged. First, those years had a lot of activity in the Gulf of Mexico, especially in the western gulf. All of those seasons had tropical systems hit land in the Western Gulf of Mexico at least 2 times. Some seasons had as many as five landfalling systems from Northern Mexico over to New Orleans. The second thing we noticed was the tendency of a tropical system to hit the west coast of Florida, particularly in the month of June. Three of our analog years, 1954, 1964, and 1973 all had that same pattern. Third, all five analog years had a tropical system travel through the Bahamas. That’s not that unusual, frankly, but we believe it’s worth watching since some of the storms in those years that went through the Bahamas either struck South Florida or the Outer Banks of North Carolina. There were hits on the Outer Banks in three of our five analog years, and a near miss in a fourth.

One final note, (we didn’t put it on the map, but it’s worth paying attention to) several storms in our analog years continued north to either Newfoundland, Canada, or the New England states of Massachusetts or Rhode Island. Those systems are much weaker that far north than in warmer waters, but they can still pack a punch, especially with copious amounts of rain and the risks to flash flooding.